The Pitcairn story by Rowland Ward who, with his wife, recently (August 2010) spent two weeks on Norfolk Island

Probably most people have heard of the mutiny against William Bligh (1754-1817) which has featured in five films and numerous articles and books. Lieut. Bligh and his crew were on an expedition backed by Sir Joseph Banks to collect breadfruit plants in Tahiti and take them to the West Indies where it was thought they would provide a cheap food source for the slaves. After several months in Tahiti the 26 metre long Bounty set sail with her 44 crew for the West Indies. After sailing some 2,000 kms a bloodless mutiny occurred led by the first mate, Fletcher Christian who had left a native white on Tahiti. The date was 28 April 1792. Bligh was an enlightened man for his times and was not harsh. However, he was dictatorial, and humiliation of Christian in front of others may have been the last straw. Picture: The Bounty

Probably most people have heard of the mutiny against William Bligh (1754-1817) which has featured in five films and numerous articles and books. Lieut. Bligh and his crew were on an expedition backed by Sir Joseph Banks to collect breadfruit plants in Tahiti and take them to the West Indies where it was thought they would provide a cheap food source for the slaves. After several months in Tahiti the 26 metre long Bounty set sail with her 44 crew for the West Indies. After sailing some 2,000 kms a bloodless mutiny occurred led by the first mate, Fletcher Christian who had left a native white on Tahiti. The date was 28 April 1792. Bligh was an enlightened man for his times and was not harsh. However, he was dictatorial, and humiliation of Christian in front of others may have been the last straw. Picture: The Bounty

Set adrift with 18 men in a 7 metre launch with no charts, a broken sextant, a pocket watch and limited provisions Bligh managed the amazing feat of sailing 5500 km to Timor via Tofua Island near where the mutiny occurred. He lost no one on the voyage, which he calculated was 6700 kms altogether, except a man who was murdered by natives on Tofua. Several men died subsequently. Bligh returned to England and his report created a sensation. Search was made in vain for the Bounty hence the saying ‘bounty hunters’.

Pitcairn Island

Meanwhile the mutineers and four loyal to Bligh returned to Tahiti where the majority remained. Nine men, led by Fletcher Christian, together with six Polynesian men and twelve Polynesian woman and a baby set off in the Bounty. On 15 January 1790 they chanced upon Pitcairn Island, which was not correctly marked on charts, and they felt safe on this tiny 4.5 sq km hideaway. They burnt the Bounty to prevent detection or desertion. Each of the sailors took a wife for himself and also divided the land into 9 parts. So there no land and only were three women for the six Polynesian men. They were treated as slaves. The sexual and racial situation was an explosive mix. Two of the sailors’ wives died so they took two of the other women. Four mutineers were killed in one day, including Fletcher Christian. Soon there were only four mutineers, ten women and some children. More violence, a suicide and one death by natural causes and in 1800 John Adams was the only mutineer left, and he was constantly drunk.

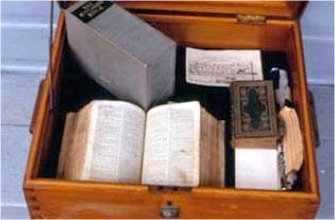

Picture: The Pitcairners’ Bible & Prayerbook

However, Adams was converted through reading the Bible and the Church of England prayer book taken from the Bounty. In 1814 a British vessel arrived and found a quiet God-fearing community led by Adams. The news caused another great sensation in England, and much interest in the Pitcairners followed, and they were often viewed through rose-coloured spectacles. In 1856 the 193 inhabitants moved to the larger Norfolk Island which had previously been a convict settlement, and is now administered as an Australia external territory. The impressive convict ruins at Kingston, just a few weeks ago declared a World Heritage site, remind one of Port Arthur.

However, Adams was converted through reading the Bible and the Church of England prayer book taken from the Bounty. In 1814 a British vessel arrived and found a quiet God-fearing community led by Adams. The news caused another great sensation in England, and much interest in the Pitcairners followed, and they were often viewed through rose-coloured spectacles. In 1856 the 193 inhabitants moved to the larger Norfolk Island which had previously been a convict settlement, and is now administered as an Australia external territory. The impressive convict ruins at Kingston, just a few weeks ago declared a World Heritage site, remind one of Port Arthur.

Move to Norfolk 1856

While some few returned to Pitcairn later, and about 50 people live on Pitcairn today, most Pitcairners remained on Norfolk where a large proportion of the permanant population of about 2,000 are descendants of the mutineers. By the 1870s the popular image of a God-fearing community was showing marks of strain. Formal adherence to Christianity could not conceal underlying problems. High Church tendencies in the Church of England of the time, and contacts through American trading vessels saw a strong Methodist movement after the death of the long-serving chaplain/leader of the community in 1884. A small Seventh-day Adventist Group soon followed. The Roman Catholic Church only came in 1957. Today the Church of England congregation is under the Diocese of Sydney. We enjoyed a good Biblical message, but the regular attendance is only 28 or 29 plus tourists. A third of the population describe themselves as C of E, but an equal number do not state or say they have no religion. Despite its remarkable origins active religious practice in the community is modest – no more than about 7% of the population on the average day of worship plus such tourists as attend.

Norfolk is still an idyllic place in terms of climate and life style. There is no port, so goods are landed by longboat and are expensive. But the land is productive, meat and fish reasonable in price, and taxes modest (no income tax or council rates, but a 12% GST). It’s not a place for children really (just about everyone on the plane with us was older than we are!), but very interesting historically, and very restful. The Gospel is preached but the people in general are content to be caring to each other but not committed to Jesus Christ. That’s not enough for them or for us. Lord, wilt thou not us revive!

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.